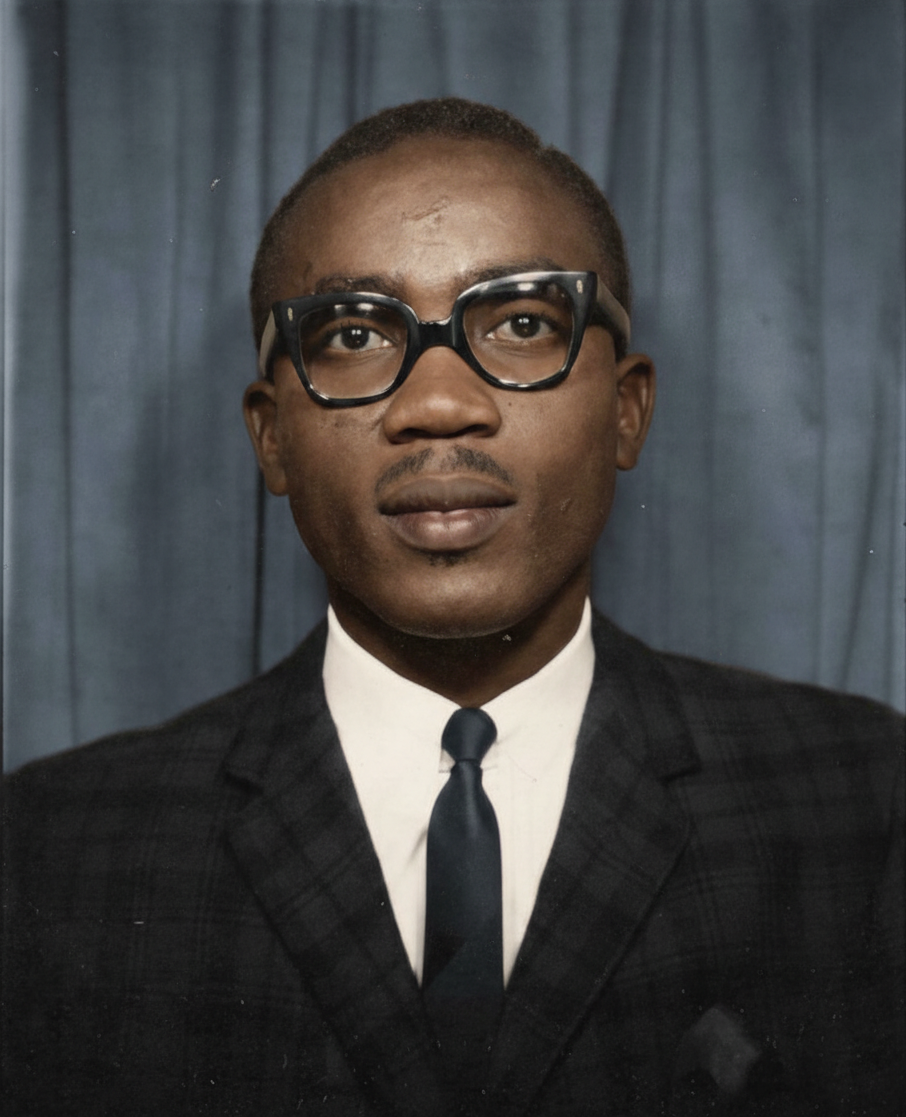

During his job interview, Winston learned he was about to make history.

In the fall of 1968, a quiet but meaningful milestone rolled through Ottawa's streets. Behind the wheel was Winston Cumberbatch, a man whose confidence, professionalism, and sense of purpose would make him the first Black bus operator in the history of OC Transpo. He didn't set out to be a trailblazer. He simply wanted stable work in a new country. But his presence opened doors that had long been closed, and his legacy continues to shape the transit system and the city he has called home for nearly six decades.

Winston's journey began on an ordinary bus ride home. He remembers watching the driver steer the large vehicle through the city with ease. "I looked at the bus driver, and I saw he was handling this big bus," he said. "And I thought, you know, I would love to do that." He had driven buses in England, but he hadn't planned to do the same in Canada. Ottawa was a civil service town, and good jobs were scarce. But something about that moment stayed with him, especially the absence of representation. "I didn't see any drivers of colour," he said. "And I thought it would be a good idea for me to drive a bus in Ottawa."

Winston didn't shy away from the responsibility. He embraced it with calm assurance.

The idea grew. It felt right. It felt possible. So, he applied to the Ottawa Transportation Commission (OTC), the predecessor to OC Transpo. During his job interview, Winston learned he was about to make history. "They told me they always wanted to employ someone of colour," he recalled. "A manager told me, 'Mr. Cumberbatch, you have all the credentials to be our first employee of colour.'"

Winston didn't shy away from the responsibility. He embraced it with calm assurance. "I had that confidence. I was just an employee looking for a job, but I knew I had a great responsibility of behaving myself wisely." His upbringing in Barbados had given him a deep sense of identity and self-worth. He carried that with him into every shift. "I had no doubts at all that I would be an asset," he said. "I even told the manager, 'Sir, I want to be an asset rather than a liability to this company.'"

His first morning on the job is etched in his memory. "You could hear a pin drop," he said. "Every eye was on me, son. Every eye."

His first morning on the job is etched in his memory. "You could hear a pin drop," he said. "Every eye was on me, son. Every eye." He felt the weight of their stares, but he also felt something else. "I believe even God was with me in that period. The confidence I had, it's hard to describe." Then came a moment of kindness that changed everything. A fellow operator approached him and said, "If I can be of any help, I want to be able to help you."

After Winston's first morning shift, he returned to the garage. The cafeteria was full, and something unexpected happened. "They called me over. Most of them wanted me to sit at their table. After that, they just accepted me." Not everyone welcomed him, some faces made that clear, but Winston chose to focus on the support rather than the resistance.

Once on the job, Winston didn't face open hostility, but subtle racism lingered.

Long before he ever stepped into the operator's seat, challenges were already forming. Some union members attempted to block the hiring of Black operators altogether. A motion was prepared to prevent it, but the union president shut it down immediately, reminding members that the union constitution protected workers of all backgrounds. Once on the job, Winston didn't face open hostility, but subtle racism lingered. "It wasn't embarrassing or insulting, but it was subtle," he said. Still, he refused to let it define his experience. He focused on what he could control: his work ethic, his professionalism, and his conduct.

A white colleague once told him, "If you had made many mistakes when you were first hired, it would have made it very difficult for management to hire future Black employees." Winston understood the weight of that responsibility, and he rose to meet it. "I got a lot of commendations from the public, the way I dressed, the way I treated the passengers, and I got no accidents," he said. His uniform was always pressed. His shoes always shined. His service always professional. "I just did my job."

He didn't set out to be a symbol, but he became one.

His presence had an immediate ripple effect. "Two months after I was hired, they employed another one," he said. "And then after that, they started applying. In one year, they employed about five or six operators of colour." Seeing Winston behind the wheel sent a message: OTC is hiring Black drivers. He didn't set out to be a symbol, but he became one.

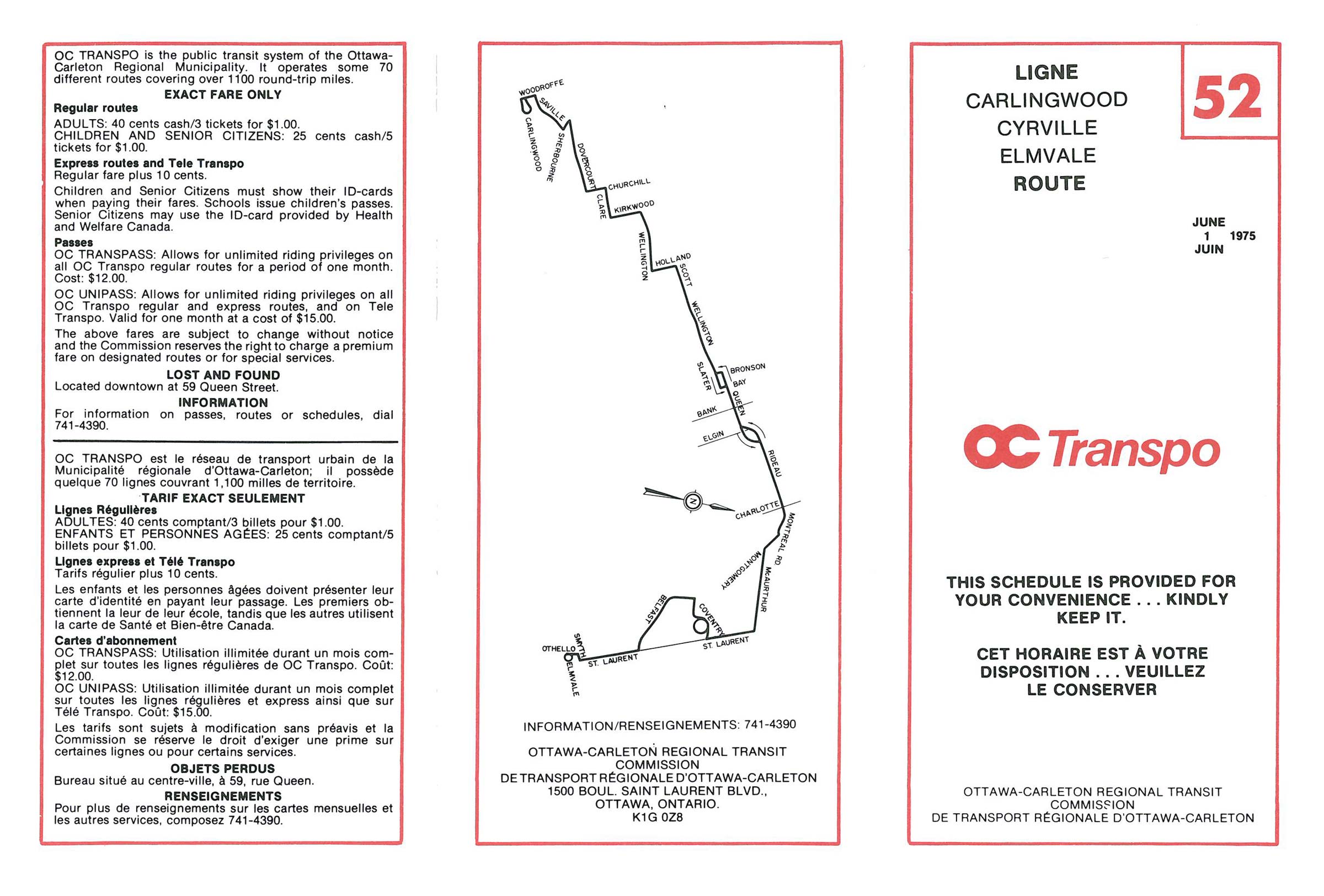

Over the years, Winston built deep connections with the people he served. Two routes stand out in his memory: the number 6 and the 52. The 52, especially, became part of his life. He knew his passengers so well that if someone was missing during the morning rush, he'd pause and look down the street. "Most of the time you'd see the passenger running, and I'd wait for them." His favorite passengers were the schoolchildren, especially a pair of Jewish siblings who rode from Dovercourt to their school on Rideau. "The brother was fascinated with me. He would sit right behind me and chat with me the whole way." Years later, the boy, now a teenager, recognized Winston on another route and greeted him warmly, even putting an arm around him. "Sometimes I wonder what became of all those kids," Winston said. "Many of them are grandparents now."

His connection to Ottawa deepened with every shift. Compared to London, England, Ottawa felt warm, friendly, and intimate. "The passengers in Ottawa, I felt a closeness," he said. "They would board the bus and say good morning." The city itself felt like home. "I felt as though I was born here. Even now, after nearly 60 years, I feel very much a part of this city." He never considered leaving. "I don't feel like a stranger. I feel as though I have always lived here."

Today, when Winston reflects on his 30-year-career, he does so with deep gratitude. "First of all, I just want to thank the management of OTC for giving me an opportunity to be part of the transit system in this city." That opportunity shaped his life. "The standard of living I enjoy is because of being an employee and a retired employee of OC Transpo, it's a reputable company, a place where you can raise a family."

In January, the Mayor formally recognized Winston for breaking barriers as OC Transpo's first Black bus operator and for paving the way toward greater equality and representation across the organization. He encourages young people seeking stability to consider OC Transpo. "If you do your job well, you will be rewarded." And as for being the first? "I have no regrets. None whatsoever. It was a pleasure, really a pleasure, a joy to be part of this company."